“I think, therefore I’m right.” Whether it’s defending a position on gun control, angling for a better grade in class or arguing about musical tastes in the lunchroom, many students tend to think that thinking about and believing in something are sufficient grounds for the truth of that something. Often, adults are no better. The whole idea of actually having strong reasons behind beliefs is noble in the abstract but requires mountains of patience and work to actually put into action. Thus, when faced with the agonizing choice, many of us stick to our hard and fast opinions rather than embrace the grueling work to justify those opinions with careful reasoning.

But opinions without reasoning don’t get us very far when we are answering essential questions, or when we want to have a productive conversation. So if we are going to be successful in both realms, we need some strategies.

There’s a strategy I’ve used for a few years now which forces students to think about (and hopefully appreciate) the wisdom of having reasons behind claims. It’s called, appropriately enough, “I think, therefore I’m right” (Unfortunately, I lost the article which outlines this strategy. When I find it, I’ll add the reference here.)

What you need:

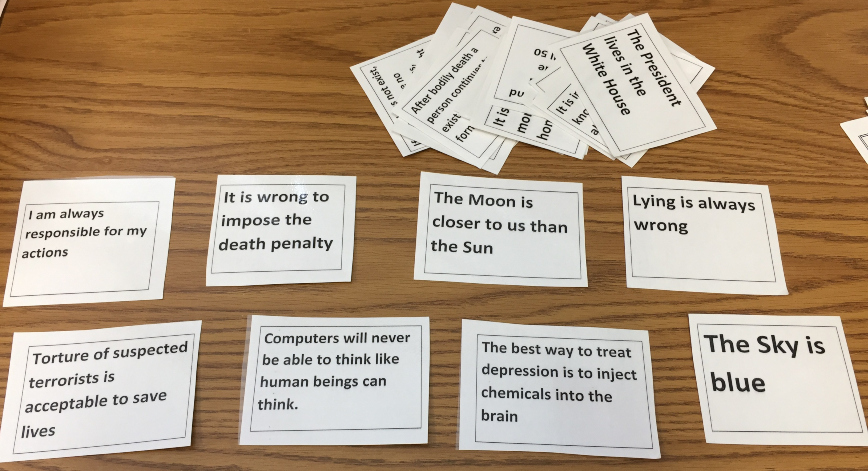

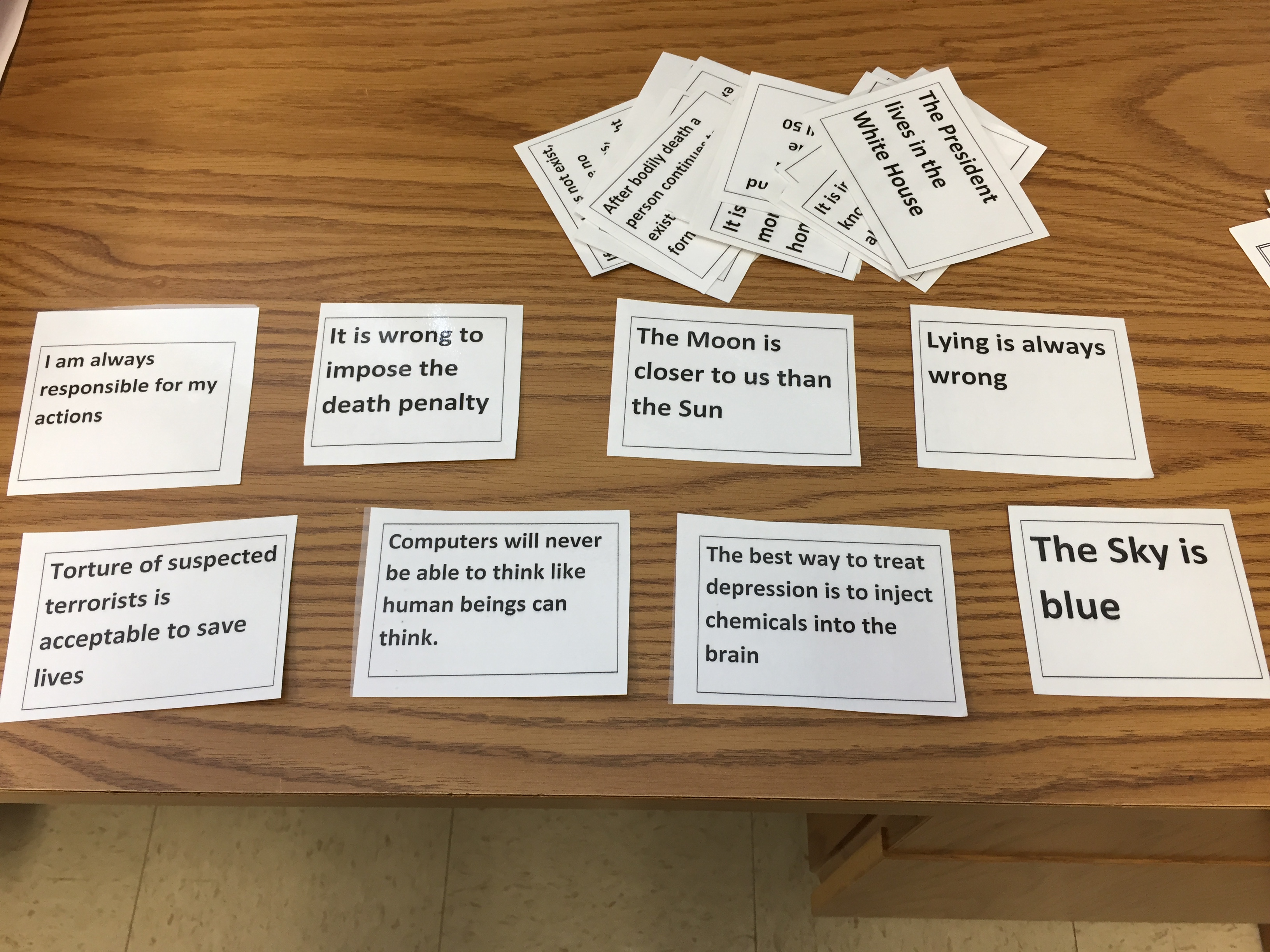

- Thirty or so unique knowledge statements ranging from the obvious to the nebulous. Put them on small slips of paper and laminate them if you can for continued use. Consider your subject area when you make your statements, although keep in mind that what the statements say is less important as to whether or not they provoke judgments from the students about whether the statements are reasonable or unreasonable. (The picture above shows a sampling of statements I use in my philosophy class– Full List Here . )

- Masking tape

Procedure:

- Make groups of 3

- Hand out 3-4 of the statements to each group. Tell group to discuss whether or not each statement is reasonable or unreasonable.

- On the board write “Reasonable” and “Unreasonable” and a line running underneath it with arrows in opposite directions.

- Tell each group to pick one statement and a student representative who, once the discussion is over, will come up to the front of the class and tape the statement onto the reasonable-unreasonable continuum in a position which best reflects his/her group’s opinion of the statement. The representative will have to provide a reason behind the opinion.

This is where it gets fun…

After the student comes up and puts the statement on the board, play Socrates and ask “Why did you place it there?” Let the student report out on the reason. Keep pressing. Whatever reason he/she gives, demand that he/she share better and better justifications for the claim. Here is how it might play out with what seemed to be an obvious statement The ultimate goal in life is to live as pleasurably as possible.

Teacher: why did you place it on the reasonable side?

Student: “because what’s the point of living life if you are in pain!”

Teacher: “have you ever suffered after something really bad happened?”

Student: “well, yes. I did really badly on an exam I didn’t study for.”

Teacher: ¨was the suffering bad for you?¨

Student : ¨Well, actually not, because it motivated me to do better.”

Teacher: ¨…so the fact that you suffered was a really important outcome, right?¨

Student: ¨Well, yes”

Imagine the conversation generated from this and other statements. They’ll love to discuss ¨Lying is always wrong,” or ¨It is wrong to impose the death penalty.¨ It is so much fun! Coax others to play Socrates and challenge other students’ beliefs too. This activity will probably spill into the next day.

Take a step back here and be careful what you are communicating…

You aren’t suggesting that there is no truth in the world. You are affirming that strong beliefs are not enough to get to truth. We need good reasons to support our thinking about all matters, big and small.

Strategies like this- combined with others like the 4-Sentence Paper— heighten student capacity to defend their claims, and counterclaims. It also gives them essential practice having conversations with each other in good faith. This is a skill to last a lifetime.