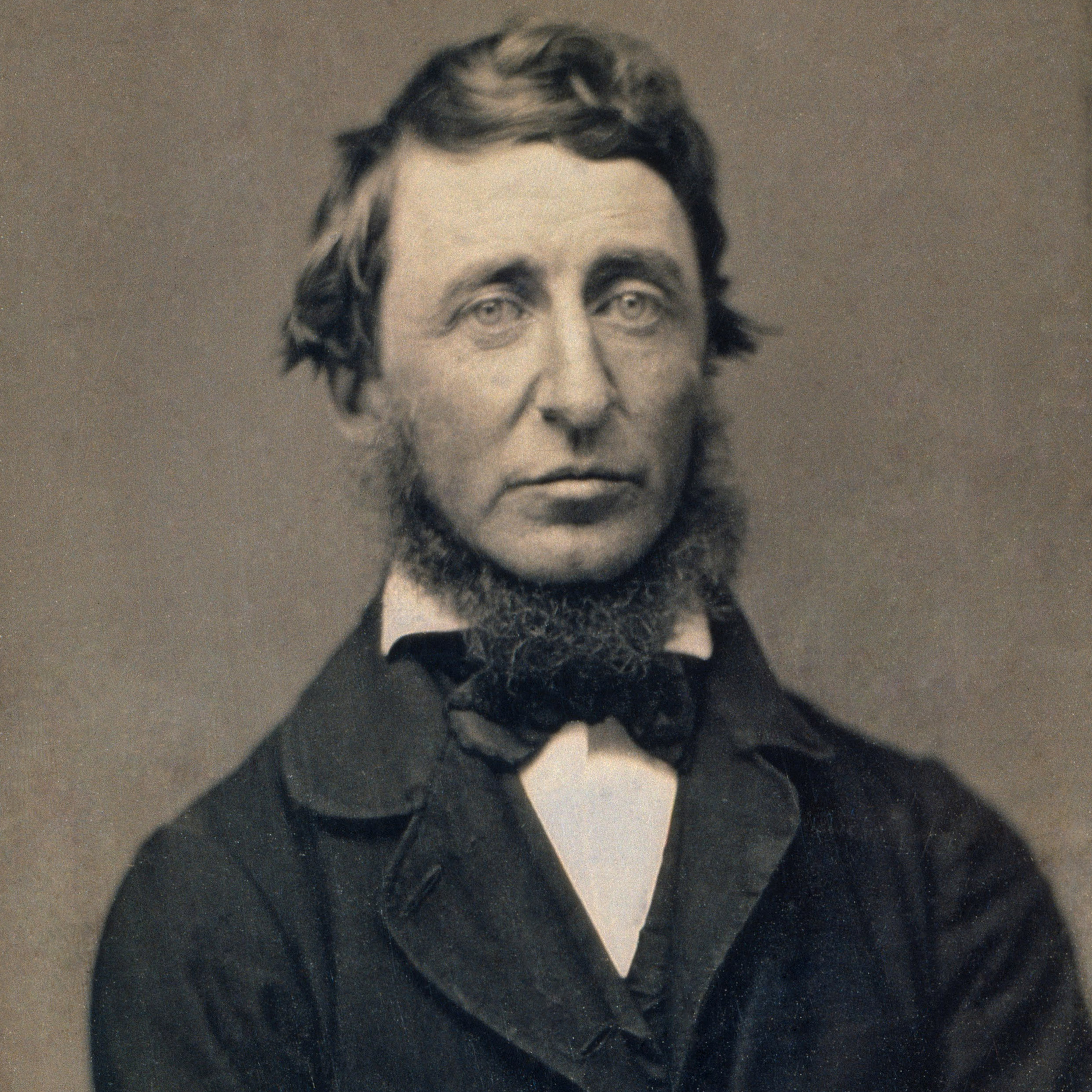

“It’s not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong, but it is his duty at least to wash his hands of it.” – With Thoreau

In this episode, Dan and Steve Fouts are joined by Mitchell Conway to explore a quote from Henry David Thoreau: “It’s not a man’s duty as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong, but it is his duty at least to wash his hands of it.” Mitchell shares his diverse experiences in education, emphasizing the importance of philosophy in teaching across various age groups. The discussion explores the role of age in philosophical discourse, the transformative potential of education, and the significance of the Teach Different Method. Together they unpack Thoreau’s views on civil disobedience, reflecting on the ethical responsibilities individuals hold in the face of injustice.

Chapters

00:00 – Introduction

00:10 – Mitch’s Background in Philosophy and Education

02:14 – The Role of Philosophy in Education

04:55 – Philosophy for All Ages

07:19 – The Misconception of Youth and Philosophy

10:24 – The Importance of Open-Mindedness

13:18 – The Teach Different Method Explained

16:22 – Thoreau’s Quote on Civil Disobedience

18:54 – Interpreting Thoreau’s Message

22:02 – Real-World Applications of Thoreau’s Ideas

24:45 – The Duty to Act Against Injustice

27:49 – The Complexity of Ethical Obligations

30:57 – Conclusion and Reflections on Responsibility

41:12 – Thoreau’s Moral Duty and Civil Disobedience

43:42 – The Complexity of Ethical Obligations

44:43 – Criteria for Opposing Injustice

46:17 – Exploring Civil Disobedience

48:57 – Philosophy Walk on Civil Disobedience

49:44 – The Role of Education in Philosophy

51:07 – Teach Different Outro

Image Source: National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Today’s Guest(s)

Transcript

Dan (00:10)

Well, welcome everybody, welcome to the Teach Different podcast we are back in action here and we have Mitch Conway with us. That’s you, and we’re totally excited about this Mitch is one of our people that we worked with in the spring for our inaugural rollout of the Teach Different Certificate Pilot he was a willing participant of that and provided great feedback and had some really good experiences, I think, using the method. And we’re just so happy to have him with us. We’re gonna ask Mitch a little bit about what he does, some of his background. He does some really interesting work with an organization out in Montana that he’ll talk about. And then at some point we’ll roll into our quote. We got Henry David Thoreau today with a theme of civil disobedience and all. That’s like a little cliffhanger. We’re going to leave that to a little bit into the conversation here. But Mitch, welcome. Please share who you are, who you work with, and your passion behind education. Take it away.

Mitch (01:20)

Yeah, thank you so much, Dan and Steve for chatting with me today. Yeah, I really enjoyed doing the training in the Teach Different Methodology in the spring. And it’s just another way into doing philosophy in the classroom. I think that’s definitely my orientation. Whatever subject I’m teaching, think I’m still a philosophy teacher. You know, I think even if I’m teaching math, I’ve found a way to admit that I’m actually teaching philosophy. But yeah, I guess, you know, I have a difficult time accounting for my various activities as an educator because it’s so various that it starts to feel absurd at a certain point. I just like I’m listing things because I’ve operated in a variety of different contexts. But I think, you know, I’ll jump in with what I’m doing most recently. So most recently, my friend Dan here and our friend Marisa, we did a workshop here in Helena, Montana with an organization called Merlin. And I’ve been working with Merlin for, I guess, four years, maybe four and a half. So, it’s a community philosophy organization. And so, one of the roles I’ve been in most consistently with that organization is facilitating monthly conversations. And it’s a group of adults who come in there of their own will to inquire into a question together to have a philosophical conversation. Me and Maurice would often co-facilitate or if she wasn’t available, I would facilitate or if I wasn’t available, she would facilitate, often we would co-facilitate these community conversations. And that’s definitely a fascinating dynamic just to be like, okay, some people know each other, some don’t know each other, but we’re talking about really, you know, really deep matters, matters that hopefully people really care about.

And I guess, you know, among my other activities, I’ve taught philosophy with quite young children, like four to seven. I’ve taught philosophy in college here in Montana at the Carroll college, I taught introductory philosophy courses. And I’ve been an educator, in an, like an agile learning center, here called Cottonwood. And so, I’ve been teaching a variety of subjects with that organization. I was just mentioning someone to last, last night, one of the first classes I did in an ongoing way with that group that they were very excited about was a death club. Now you’d be wondering like, okay, that sounds sort of weird. What do you mean you were doing a death club with high school students, Mitch? But they wanted to talk about death and dying. And so, you know, we went and walked around in graveyards and talked about what happens when we die. We went and, you know, we met with a grief counselor. We met with a funeral director and had in-depth conversations, philosophical conversations with those folks. And that was just a fantastic experience. The students were so, I mean, they chose it. And so, they were very excited to be a part of it. But also I have a long background, you could say, as a theater educator. So, I was working in theater for a number of years, and I’ve used a variety of different forms as a theater educator and that definitely plays a major role in my general practice as an educator. Certainly in the philosophy classroom, I know I use those tools quite a bit. So that’s an attempt to say something about my experience as an educator. I don’t know if I addressed what you said about like, well, why I’m passionate about it. That’s an interesting one. I guess whether or not it’s warranted, I have the hope that the sorts of educational projects I’m involved with can be transformative in a personal way to the students or the people who are engaged with them. So oftentimes people think about schooling as something that’s like, well, you want to acquire skills and then be able to acquire a job that, you know, those skills are involved in that. And that’s sort of what your project is when you’re involved in schooling. I don’t mean to devalue that or neglect the fact that that’s an essential element to good schooling is preparing one for one’s professional life. But I guess what I really connect to is when I feel like someone is growing as an individual in the sense of they’re becoming more authentic. Or gaining self-knowledge or jettisoning beliefs that are upon reflection, not sufficiently founded or those sorts of things. I like being involved in those sorts of processes and I think that’s why I’m in education.

Dan (06:02)

That’s great. And that’s of any age, right? I mean, you appreciate that growth and development no matter what the age. Yeah. And it was a pleasure, to facilitate with you and Marisa and Helena. We had that really good conversation with a variety of aged people. And yeah, I saw you in action. You’re quite impressive.

Mitch (06:10)

Definitely. Definitely. Yeah. Kind of you just –

Steve (06:31)

Mitch, I have a question for you with regard to the different age levels. We were talking about this briefly before the podcast, the different age levels of people that get introduced to philosophy and what we might call adult-like conversations, some more sublime, serious conversations that rely on human experience at times to really appreciate, especially some of the moral questions, because the longer you have been on the earth, probably the more mistakes you’ve made and also the more chances you’ve gotten to see what it’s like to not make mistakes or to see other people make mistakes. And that feeds into a lot of like really good ideas about philosophy, especially moral philosophy. Here’s my question, why do you think that many people think that younger people aren’t really ready for deep thinking and philosophical introspection? And I mean people, they’ll argue that a 17 year old is too young or a 16 year old because philosophy isn’t in most high schools. Where do you see that sentiment coming from? And I’m going to, I’m sure you disagree with it like I do, but where does it come from?

Mitch (07:51)

Right. Well, there could be a few different things going on with it with different people, but at least one idea, you know, and I don’t want to say this wrong and like it come out in a dismissive way. But when people get really, really elderly, it’s like, what’s the role in the community? And so maybe people start saying like, well, I get that they have a lot of experience of being alive and so they’re wise. Now, I’d be willing to say that sometimes people who are old are wise and grant that. OK, that’s fine. But it’s not a given that people who are older will be wise. I’ve seen, as I’m sure many of us have, many cases when that does not apply, when people haven’t learned from their mistakes and from their experiences. They’ll repeat the same mistakes over and over. And so, there’s this problem where it’s like, well, someone has more experiences, whatever that word means, more they’ve undergone, more like you said, Steve. More mistakes they’ve made and hopefully have the opportunity to learn from. But because it’s really hard to see when someone has developed as a person, like sometimes there’s obvious transformations, right? But when we go through these little mistakes and we learn from them, it’s hard to see when someone actually has like, actually this person is, you know, talking more politely to the person in the grocery store, whatever those little moments are, right? We don’t get to see that. And so, it might be a perceptual problem where it’s like, well, how does someone think about the matters that are really challenging for us in depth, but more matters that are really challenging for, about the human experience. And so, it’s likely that if someone has more experience that they have more to say about that. But I don’t, in my experience, that is not the case. That is not the case. And so, I wouldn’t even be willing to say that it’s more likely that if someone is older, then they’re gonna do philosophy better.

I wouldn’t even be willing to give some sort of trend along with it because I’ve talked with four and five year olds who are very good at it. And that’s because, and one reason that they can be quite good at it is because they’re open-minded and because they’re curious. And being open-minded and curious are essential to philosophizing. In contrast to advising on how to execute some particular task or how to accomplish something or so forth. And it tends to be the case, in my opinion, it’s harder for people as they age to remain open-minded and curious. So, I guess the other, what I guess I’m coming around to saying in response to your question, Steve, is that why people would think that it’s only those who are older can philosophize is actually a misunderstanding about what wisdom is. It’s actually this assumption that like, what we do is we like accumulate a pile of experience and then we know things and then we’re like doing better. But I think whether fortunately or unfortunately, when it comes to some of these really deep matters, we don’t know about them in a fundamental way. We actually can’t know in a solid way. And accepting that we can’t know is something that someone who’s open-minded and curious about learning more is more likely to be able to acknowledge. Have I somewhat answered your question?

Dan (11:53)

Yeah, so from what I’m hearing, Mitch, you’re saying the dispositions of philosophy, the curiosity, the open mindedness, the almost the advantage of not having a lot of experiences are actually dispositions of the youth more than the elderly. And so, in that way, kids are more conducive to philosophical thinking. I love how you frame that. I think you’re absolutely right.

Mitch (12:13)

Yes.

Dan (12:23)

I mean, I teach it in high school, as you know, Mitch, and kids not only can think like this, they want to think like this. They do not have many jaded opinions yet. There’s still a lot of hope and a lot of interest in shaping a new way of thinking in a high school classroom. There’s that energy that you don’t have in other groups. So, 100 % agree.

Mitch (12:52)

Has anyone, if I may interrupt just for a second, I don’t have children, but I can say that, you know, I assume that many people who’ve had children have noticed their kid get into something and then they’re totally into it right away. And it’s like this thing where they’ve like just started out and then they’re like, this thing. And they’re like all about that thing for like a long stretch of time, right? And so, I think that sort of experience that many people have had and can hopefully help people to see what you were just talking about, Dan, that actually young people can be like really change quite readily, right? In terms of what their interest is. And so be more available to altering their judgments. Anyways, Steve, you were gonna say something else.

Steve (13:35)

No, I really enjoyed that too, because that would be wonderful. And that’s an environmental thing. If you’re around a teacher, if you’re around an environment where that’s brought out, wow, that increases the likelihood. My thought was this. Experience doesn’t equate with discernment.

You can be experienced, you can live a long time with your eyes closed. So, what I heard from you, Mitch, and the way I’m understanding it, I understand a lot of things through Plato’s allegory of the cave, which talks about how all human beings are born and chained and are forced to look at the wall inside a cave that they don’t even realize they’re in, and there’s a puppet show behind them and a fire burning. So they’re watching all these artifacts on the wall. They think that’s reality because people are talking behind them, but it’s echoing off the wall. So they’re not even getting the direct audio. Everything is distorted, but to them, it’s clear. You can live a life in the cave and still have no idea you’re in a cave. Philosophy is all about the ascent out of the cave and the realization that there’s another reality that you’re not considering that gives you perspective of the reality that you were born in. So anyway, I’m just throwing that out because it’s the gift that keeps on giving to me to understand philosophy. I hope it made sense with your way of thinking of experience.

Mitch (15:25)

Well, you know, if I think about the cave, I mean, it’s really hard in the to like, it’s really complex the way it’s utilized in the context in the Republic. So, abstracting from that for a moment, at least taking the image on its own, you know, we can think of it like, well, okay, I have lived a life based on certain assumptions or according to certain conventions, or I’ve taken certain opinions to be true, which are like those images on the wall and the ascent is so sort of challenging of those presuppositions. But also it seems and sort of like as though that happens one time. But it seems to me like a perpetual problem that we have where we like establish conceptions or ways of understanding or something like that. And we have to like rework them and reassess them and like not get embedded in thinking that we grasp reality, because actually reality is really hard. You know, you could say like, well, there’s the superficial thing. There’s like the deep in the cave shadow thing that we think is real, but it’s in fact not real. But actually, you know, and in the image, you know, it’s a very painful thing to see reality. And I think many of us have experienced, you know, running up against reality in that sort of way. Ouch. Okay. And just Yeah. Okay.

Steve (16:46)

Which is why we go back. I’m sorry, Mitch, I just, I think which is why we go back to the shadows. You know, Plato talks about this leaving, coming back, leaving again, you know, like, like you’re saying, it’s not a one size fits all when you move to one side or the other. It’s a, there’s a dynamic there. So yes, I follow.

Mitch (17:11)

Yeah, and I know the cycle, a cycle of it isn’t in the way that Plato uses it, but in the sense that you described where it’s like, well, you could do go back down, right, like someone who has gone on that journey of ascent out of the cave does go back down to bring other people, you know, to like be like, hey, this is not, you know, the right way to think or this.

Steve (17:32)

There’s something else.

Dan (17:32)

The obligation, there’s a duty to come back.

Mitch (17:35)

Yeah, yeah, I think so. I think so.

Steve (17:40)

We could go off on that one. We got a Thoreau though, right? I mean…

Dan (17:42)

Yeah, that’s great. Yeah, I mean, what do you say we do? Well, I mean, this kind of what we’re talking about here of seeing the light, so to speak, and not being not being seduced by opinions and things that have not been thought about and having lack of discernment. I mean, one of the hopes for this this method, this Teach Different Method is to help people engage with ideas in ways where they do open their mind up and they’re not immediately convinced of one way to think of the world. They stop, they consider, they listen, and they maybe alter their opinions based on a new reality and new evidence. I mean, that’s the hope. And I think it’s a skill, it’s a disposition that we try to engender with it. Is that, yeah, I was just gonna say.

Steve (18:39)

Mitch I would love your read on what is –

Dan (18:42)

What is your read on that?

Steve (18:42)

I would love to hear you describe the Teach Different Method as in the way that it hopefully adds to philosophy. Just the way that you see it working and what you usually don’t see in many skills or tools that were taught as teachers. I would love to hear your take.

Mitch (18:49)

Yeah, right on. I mean, I definitely agree with what Dan was just saying about this invitation to see things from multiple perspectives. I think that’s something that’s so in the first step, you have to like articulate what the quote saying in your own way. Right. And I think that’s something so often people fail to do just in one on one communication and then proceed from misunderstandings right there. It’s like, oh, you said something and I think I know what you said. And so, I’m responding to what I think you said. And then we get an argument because of something that’s like, and then it comes down to you being like, I didn’t I didn’t mean that. I mean, I meant this, you know, because I’m working with young kids at a camp right now. They’re doing that all the time. It’s like, no, you said I didn’t say that to you. And it’s like, you were okay. And so there is something healthy just to that act of rearticulation as an ongoing practice. It’s like, Okay, well, how would I say this for myself? Is that does that match? Does that match? What are the differences between these? And then again, this is what Dan was emphasizing, think is like, well, okay, what’s the way on which, what’s one way in which one could disagree with this? And I’m not saying how I disagree with it. I’m saying a way in which someone could disagree with it. I’m sort of like putting aside for a moment my own judgments about a particular matter at hand and saying like, well, what are the different ways in? And then I’m starting to think more, perhaps objectively, perhaps, like Dan said, thinking things from different angles. And that stage usually in the process from what I’ve done and what I’ve heard from you guys is that you’ll hear many different people’s opinions about that. You’ll hear, okay, what are the different ways that you all pose that you would disagree with this? And so I’m already invited into thinking about things from many different viewpoints before delving into a place of inquiring.

Um, and the other thing I think is really, you know, is not as often utilized as a tool, um, in philosophy, but I think very much has a place is, is personal narrative as a way into ideas. And it seems like that’s a major consistent, even if not every time you address a quote, you’re utilizing that as a component of your practice. seems like a consistent component of your practice that you’re inviting students to think through their personal experience as a way into the idea and that there’s something, um, that grounds one in it, that you’re not gonna be as inclined to make arguments that don’t really add up, that start to veer off into some theoretical rabbit hole that gets lost in something if you’ve grounded it in your own problems. Like, okay, this proposition or this problem as it’s supposed in a quote has relevance to me. And I can resonate with that. And then, okay, what’s going on with it? What are my judgments about it? So, I think I’ve just been sort of in restating components of the method identified things that I think are not necessarily done in a consistent manner in classroom discussion. And the other one that I think is really worth noting, and this is definitely prominent in the workshop that Dan and Marisa and I did the other day where when Dan was initially inviting people to, in his facilitation, he was very much encouraging people to talk to each other rather than, one person says something, he responds, then he calls on the next person. And I think very often educators can fall into that trap, that trap of like, it has to always go through me. I’m the one who’s mediating this whole thing. And by mediating, I mean that I respond to each thing and then every student is talking to me. But actually to create a space in which the students are thinking together, responding to each other, I think is a really, really significant difference in the classroom dynamic and in a positive way.

Steve (23:01)

Really appreciated that and.

Dan (23:01)

That’s great. I think I hear Thoreau knocking at the door. Are we ready? Are we ready? Okay, let’s, that was it. Now this is a longer quote, so we’re going to say this multiple times to the listeners out there. I’ll read it twice. It is not a man’s duty as a matter of course to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong, but it is his duty at least to wash his hands of it. One more time. It is not a man’s duty as a matter of course to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong, but it is his duty at least to wash his hands of it. Thank you Thoreau from his essay on civil disobedience, 1949 I believe. I got that date right. Excuse me, 1849.

Steve (24:11)

Right before the Civil War.

Dan (24:13)

And he’s responding to slavery and the Mexican-American war. All right, who wants to take the claim in their own words here?

Mitch (24:25)

I’ll try, I’ll try. So. And I, you know, I’m cheating in that I’ve read the whole essay. maybe some, you know, I’ve, know some other things he said, so I’m just acknowledging that that’s playing into my thinking right now in my, restating it. But, it’s something like, well, and I might be adding in something with, with this, but I’m going to try it nonetheless. I can’t do everything. I cannot, uh, with my limited capacities and time on earth address all wrongs done on this earth. It’s just beyond my capacity. So again, I’m trying to restate what I know in my own way, what I think Thoreau is emphasizing here, not expressing that I agree with it, just saying that it is to restating it. And so because I can’t do everything, the sphere of my ethical obligations extends to what I have agency in, or rather, injustices that I play some sort of part in. That’s where my responsibilities are. And I have to, if I’m going to be an ethical human being, separate myself from those acts of injustice, whether, know, certainly not to the myself, but also if they’re being done by others and I’m complicit in those actions in some way to make sure that I’m not supporting those injustices. I’d said it much longer ways.

Steve (26:06)

You nailed it though. mean, I got, I came up with this idea of no one’s obligated to fight against every injustice, but it’s like your duty to not support injustice, you know, back to your agency issue or notion. If you know that you doing things or not doing things are going to add to something that’s going to happen that’s going to be bad and you have the power to choose to stop it or continue something else. It’s your obligation to, but that doesn’t mean you have to fight everything. You know, you can, I’m thinking of good Samaritan laws in Britain, for instance, where if you go by the road and you see someone get attacked or you see someone bleeding on the side of the road and you drive by, you can get arrested for not addressing that injustice. But I think that this claim is really just making a distinction. It’s an interesting distinction and I’d like to hear some examples that anyone has in mind.

Dan (27:16)

Okay. Yeah, speaking of examples and the spirit of personal experiences, the first, I think you guys articulated the claim really well. can’t eradicate every evil in the world, but you shouldn’t participate in it. You said agency, Mitch. I like that. Like whatever you have control over in your own life, you should make sure that you do not participate in something that is that is evil. So I think of like take climate change. It might not be our duty to eliminate climate change entirely, but that also may mean that it is our duty to ride our bike more and not participate in fossil fuel.

Mitch (28:12)

Right.

Dan (28:13)

So maybe there’s a duty there that’s individual not to eradicate the whole thing, but to do something about it. I don’t know if that personal experience fits here.

Mitch (28:24)

I think so. I think so.

Steve (28:26)

Yeah, I mean that in a way that’s the same issue. You know, climate change on a global scale and then something you can do to acknowledge climate change. I immediately came to a personal situation where maybe a friend of yours is cheating on his girlfriend. That’s none of your business. Okay. Like it’s not good that he’s doing it. You may be hurting him and her by not blowing the whistle. I mean, you could argue that, but still I think that this would claim that that’s not your business. However, if I’m trying to think of a condition that would make it your business. Probably if you were the one that they were cheating with. I mean, you know, I’m just trying to think of a different condition with that. Maybe I ran out of gas with this example.

Mitch (29:17)

You’re good. Well, that’s a hard because it depends on so many different factors. And it could be that you not saying anything perpetuates it happening, but otherwise it would. And so actually you have a role in it continuing to go. And so, it is your business. You know, it’s not like it’s, I, if it’s someone you care about, right. If, or if it’s a couple that you care.

Dan (29:25)

Yeah.

Steve (29:47)

I could see someone arguing that for sure. Bad example, next.

Mitch (29:50)

Yeah.

Dan (29:54)

Well, how about, okay, just bullying. You know, you could, it’s not your duty to eliminate bullying in a, I’m thinking of something that a high school student would connect with. It’s not your duty to eradicate the mistreatment of people and bullying, but that does not mean you don’t have a duty to resist the temptation yourself.

Mitch (30:03)

Yeah.

Dan (30:22)

You can’t eradicate everything, but you have agency over your own behavior to not perpetuate it.

Mitch (30:29)

Right. And the same thing, the same thing would apply if we connect Steve’s directions to the good Samaritan idea to bullying that. In fact, if you see it happening, right. Even if you’re not the one doing it, then you have an obligation. Then it’s like, okay, like, I don’t know if you’ve been this situation, you have to break up fights. And it’s like, I don’t know these, I do not know these children, but I am, I’m, you are fighting and I am going to make you not fight because you are fighting in the street. And like I’m, you know, sometimes that feels dangerous, but it’s also like, well, what am I going to do? I’m here. You were in high school. I’m, you know, wearing a suit. you look at me like I’m doing something different, you know? And so, I put myself between you and then you’re going to stop doing it. And it’s like, think, I think we do have that just because we’re in the situation, then it is our responsibility. So, I think there is something to that good Samaritan idea that is even just running across something like, like, even if you hear, okay, you hear about your friend cheating on girlfriend or whatever. As soon as then you are involved, you get involved just by like, I don’t know. That’s I think one of the problems with this quote is thinking about what is the arena for our involvement? Like when does it fall?

Steve (31:40)

There’s your essential question,

Dan (31:41)

Good, an essential question.

Steve (31:42)

The beginning of it. Where are those boundaries? How do you define involvement? Can we bring this to a societal level when we see, let’s treat this issue of immigration a little bit and some of the arrests that are being made of certain illegal immigrants in certain places under certain conditions.

Mitch (31:46)

Yeah.

Steve (32:10)

That some people at least perceive to be unconstitutional and wrong and immoral. Are they thinking that they have to react to that? Whereas some people are saying, that’s just an injustice. That may be wrong, Martha, but I’m here watching TV with you. I’m not gonna go out in the streets, but I’m definitely gonna tell your brother that it’s wrong on Thanksgiving, you know, I’m just trying to, where do you? I’m back to your essential question, Mitch. Where do you draw the line? What Martin Luther King said, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. He might disagree with this claim.

Mitch (33:01)

I think he would. I think he would discuss Thoreau mean, the beginning of the quote says it’s not once I’m not remembering the exact wording, but to the eradication of any, even the most egregious role. And that one’s actually really hard to stomach if you take it in a certain way, if you take it as like, well, the most egregious wrong. it’s like, depending on what I mean by like, it’s not my business, right? Like, I hear about it, but it’s, but it’s like, I’m not doing it like Dan was saying with the example of bullying. Well, if I’m not the one bullying, you know, then then hands off. I don’t have any obligations.

Dan (33:40)

It doesn’t concern me. Why would I objectify it and be bothered by it? I’m not participating in it. I’ve absolved myself of responsibility. Sounds a little absurd, doesn’t it?

Mitch (33:46)

Yeah.

Steve (33:53)

Boy, and I’m gonna fall into your trap, Mitch, of knowing a little bit about Thoreau and how he separated himself from society for a long period of time and kind of wiped his hands from that connection that some people believe is just part of being human. You have your individuality, but you also are part of a social fabric. Everybody came from a mother. You know, and you are part of something regardless of whether or not you think you are and you’re wrapped up in them. It’s not as easy to say that an injustice doesn’t affect you. And I’m thinking of another quote we’ve done with the African proverb. Damn, remember that? ⁓ I am because you are. Just the whole idea of our identities are wrapped up into other people and it’s really not fair to think of separating your involvement arbitrarily.

Mitch (34:57)

Yeah. Yeah. I mean, if we think about the immigration example that you brought up, Steve, it’s like maybe people make the move of like, even if I’ve worked with this person or like in my community in some capacity, they make the person who’s like saying, this is not my business. Right. Says like, well, OK, they were here, but they weren’t really part of my community.

They reach that sort of conclusion in order to justify the position like, well, they didn’t come in in the right way. And so even if I’ve interacted with them as a part of this community I’m in, they weren’t really rightfully a part of it. And that would be the basis on which they say, OK, I don’t have an obligation there. But that one is a little weird. As soon as you start to think like, well, what are the boundaries with that one? How long have I been getting this person to fix my car before I’m like, hey, what are you doing? If it’s six months, I’m like, well, okay, they just got here. If it’s five years, I’m like, well, five years. If it’s 35 years, am I like, well, what’s going on with that? Yeah.

Dan (36:16)

So succinctly then, what would the counterclaim be? This is saying, is not a man’s duty to devote, I’m gonna compress it a little bit. It’s not a man’s duty to devote himself to the eradication of any wrong. Well, counterclaim, it is a person’s duty to devote yourself to the eradication of a wrong. That is your duty Independent of how it impacts you individually or your neighbors, you have a larger obligation that you should act on, right?

Mitch (36:56)

Yeah, yeah.

Dan (36:58)

That’s where I think Dr. Martin Luther King would land on this.

Steve (37:04)

You have a duty to fight injustice. Now, anywhere, right? And some people think like this. I think it’s fair to bring up the last part though of his quote that we haven’t really focused on yet. It is his duty to wash his hands of it. So it sounds like Thoreau is saying, you don’t have to fight every injustice, but you do have a duty that if you feel that your silence, for instance, is going to make this injustice continue, you have a duty to speak up. So I think that maybe we could give Thoreau a little bit more credit here. In the sense that if you’re an individual who sees yourself as connected to a larger social fabric, a Martin Luther King Jr., and you are going to, I’m starting to buy into this one a little bit more. Could someone pick that up?

Dan (38:18)

I, well, just to, would, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is not here to validate how we’re talking about, but I would make an argument that he would agree with both of these, that you have a duty to eradicate evil on a large scale, and you have the duty to wash your hands of it and not participate in it.

Mitch (38:47)

I mean, it is hard to say like, we’re bound up in so many networks of wrongdoing constantly. I don’t know if that’s your thought or your experience, but that is my experience that I’m in all of these networks of things that I’m concerned about their ethical implications. And so there is something that’s overwhelming about like even washing my hands of my own of the wrongs that I am involved in, let alone addressing those other that are you know that I have no hand in

Dan (39:24)

Gosh, it just brought up another example that kind of links to the claim when people speak of whether or not to purchase clothing that is made in countries in violation of labor laws. You could say, well, it’s not my duty to eradicate that on a large scale, but I can keep my money in my pocket and not buy it and support it in that way. So I’m kind of back to

Steve (39:24)

Very involved. Okay, you’re definitely are. I see your theme in the way that you’re looking at this. Yeah, you don’t have to go get a plane and go to China and start investigating these factories. But you can’t stop buying this stuff. You definitely can wash your hands of it.

Dan (39:54)

with Thoreau’s kind of saying here.

Mitch (40:13)

And maybe there’s something to like, well, what is what is your duty in the sense that you really have an obligation to act in a particular sort of way? Like, you know, this about the factory, you really, upon ethical consideration, really do feel like you can’t buy from that factory. But even if it’s not your duty to go fly to the factory, it’s still something you could do. It’s still something that would be something that could accomplish some great good to fly to the factory. And so maybe there’s a distinction there between the sorts of ethical behaviors that really, it’s requisites that we act upon or that we remove ourselves from certain sorts of dynamics and those which we can also engage in, which have value in their own right, even if they’re not duties. I know. I think there are some folks who would strongly disagree with what I just said.

Steve (41:11)

I know what you mean. And again, Henry David Thoreau, the more I look at this quote, it’s not a man’s duty as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous wrong, but it is his duty at least to wash his hands of it. At the very least, Thoreau lived this because I think he did see a society that was corrupt and was evil in a lot of different ways. And he’s looking for, I don’t want to get too psychological, but he needs a reason why it’s okay to leave it and wash his hands of it because he did have a sense of duty that he didn’t want to get himself wrapped up in it. I’m just, you know, again.

Dan (41:59)

Right. So if slavery is the context in which he’s writing this, he’s saying, I’m not going to participate in slavery. I’m going to wash my hands of that terrible, immoral institution. That’s what I can do.

Mitch (42:16)

But you know, it’s so hard because like, even throws maybe an extreme example because he refuses to pay his taxes, right? He’s like, I’m not going to pay taxes because it’s important. And so even people argue like, it didn’t actually go to the, wouldn’t have actually gone to the federal government, the tax he didn’t pay, but fine. Like, let’s say that it is like, okay signifying his allegiance to the government in some way to pay taxes and he refuses to do that. But like, let’s say, okay, he’s growing his own apples. He’s, you know, shooting his own squirrels for meat. And he’s like, you doing whatever he does to survive. He’s still probably, you know, even if he’s making his own soap or something, he’s got to go to town to like do some stuff. Right. And so depending on like his judgments about that, the governmental entity that he is he is associated with, or rather what I mean to say is how severe are the judgments that he makes about it? How evil, how corrupt does he think that that government is? Does he have an obligation not just to be like, I’m going to grow my own apples and I’m not going to live in town, I’m going to live at Walden, but rather to leave entirely because he is still bound up in these networks that he’s in proximity with, which are in some ways subsidizing or even acting directly to support this government.

Dan (43:42)

Well said.

Steve (43:45)

And you said, shoot a squirrel. And I was thinking, Mitch, who made the gun? It is tough to get away from the benefits of living together and society fabric. Impossible, right? Come on. Yeah.

Mitch (43:49)

Yeah, right, Exactly. Need a little gun? No, exactly. Impossible.

Dan (44:02)

Now,

Mitch (44:03)

No way.

Dan (44:04)

What, if any, lingering questions that come from this?

Mitch (44:15)

I mean, for throw, we stop paying taxes. How, how evil does your government have to be before you stop paying taxes and think that that’s a reasonable action? People, cause we’re in a democracy. So, there’s constantly matters of debate. There’s constantly things that a majority might read a particular judgment about, which differs from your judgment. And we’re sort of oftentimes conceding to the will of the majority and feeling like, okay, this is what people wanted and what people’s general judgment about what a good policy is and it differs from mine. And so, I’m not going to, you know, refuse to pay taxes because I still respect the principle of democracy. Or there are cases when in fact the majority does something so heinous that you feel like it overrides your commitment to that democracy. And you’re like, well, I’m not, I’m not paying. mean, taxes is just an example.

Steve (45:09)

Yeah, can’t buy into this. Here’s, yeah, go ahead.

Dan (45:11)

How do I know? Go ahead, Steve. How do I know which injustices I should try to get rid of?

Steve (45:23)

When is the name?

Dan (45:24)

How do I know which injustices I should fight against?

Steve (45:29)

What’s the criteria maybe? In my mind it’s similar. It’s like when are individuals responsible for opposing injustice? What’s the criteria? What’s the red line?

Mitch (45:49)

Yeah, and I’m gonna answer. I feel like I want to say always. I want to say always and just like it matters what medium or what sort of act is involved in that opposition and the nature of the injustice would inform what sort of act one would take in relation to that injustice. given injustice, think always we are called to act in response to.

Dan (46:17)

Great. You know, Mitch, before I forget, you’re doing a philosophy walk on civil disobedience in Helena, Montana in a few days. Do you want to give a little preview of that? Like, what are you going to do for three hours with this community? Yeah. This is a pitch for Merlin here.

Steve (46:32)

What’s a philosophy walk?

Mitch (46:35)

Yeah. So this is with the organization. Yeah. So I mentioned Berlin, the community philosophy organization I work with earlier. And so, we’re doing a walk on Saturday. And so, I guess the preview is we’re going to talk about in general, the idea of civil disobedience, just as like a way of addressing injustice as, like a, an approach, cause it’s quite distinctive, you know, from armed rebellion, for example, like, okay, there’s the American Revolution, they justified that revolution in relation to the British crown based on such and such. And the context in which people have decided to utilize civil disobedience as an approach to injustice, or I guess, not so much those different contexts, but rather, it’s a very different approach from that, from that approach. So one is just talk about what it is in the different historical instances of it. And Thoreau is definitely one. His essay is certainly foundational on this. But then to think about, yeah, what do we do when there are unjust laws? When there are laws that are unjust, what do we do? Because there’s a variety of different options. Thoreau says, well, you can’t just be like, well, it’s not my business, so I’m just going to obey it. I’m not deciding that at all. You know, I can’t control it. Do you have an obligation to try to change it? Right. If you feel like it’s an unjust law to do something through, through the typical channels to alter policy, like the calling your, you know, Senator or, you know, voting or even lobbying or whatever, these sorts of things. Or do you have an obligation because it is an unjust, unjust law to transgress it right away. To be like, I’m not, I’m going to break that law. I’m to support that law being broken right away because it’s unjust and my commitment is to justice over law. Now, whenever, when those things come into competition. So I’m saying that as like some of the, and there’s a variety of ways in which you could transgress those laws is civil disobedience. Others are, you know, like, okay, there’s a revolution and so forth. And so just that’s one thing we’ll be thinking about is like, what, yeah, what do we do? What do we do when there are laws that are unjust. And then we’ll also be thinking about some of these ethical considerations we’ve been weighing in relation to this quote together. Sort of what is the sphere of our ethical responsibilities in the context of a democracy? How does that alter the way in which we respond to or act upon our own judgments about right and wrong in the community we’re a part of? Yeah.

Dan (49:22)

That’s great. That’s great. And just to give a plug to Merlin, it’s merlinccc.org. And as I understand it, Mitch, Marisa and you end up uploading a lot of different resources from these walks and events. So, people can check that out if they’re interested.

Mitch (49:30)

You got it. Yeah, there’s quite an archive of different materials that Marisa has put together on the website from different symposia that Merlin has organized from different events that have happened over the past decade with the organization. And there’s a lot of materials also if you’re just interested in philosophy. There’s some really cool materials just about some particular aspects of philosophy that I think are really cool.

Dan (50:08)

Awesome. Well, Mitch, this has been a really great discussion. It’s so good to see you again. And thanks again for participating in the spring in our certificate pilot. And we’re looking forward to working with you on Into the Future. Got a lot of exciting things going on. Thanks so much. Really appreciate it.

Mitch (50:28)

Thank you so much, Dan and Steve for what you do. Just like the care you show for being good teachers and sort of like being in a position of advocating for something you feel like is going to be transformative to classrooms. We need that sort of care for education. It so gets thrown on the back burner of the sorts of things people are concerned about. And it’s just like, you just throw your child into school. And so to be deeply thinking about what’s going to make education better, just thank you for being in place.

Steve (50:56)

You’re welcome in and Remy, my cat decided to come up here when you talked about the philosophy walk. It was great Mitch though. It was a pleasure.

Mitch (51:03)

Yeah.